How do we harness current technology to make the most impact to modern biology and medicine? This question is as wide as the expertise of our group. We work in an interdisciplinary manner, covering areas from computer science to molecular biology. We like technology, and we are not afraid to explore the unknown. We are a member of UCMR (Umeå centre for microbial research) as well as Icelab (Integrated science lab). We believe the key to success is to collaborate with others, build critical mass, and exploit opportunities.

Can we phenotype with higher precision?

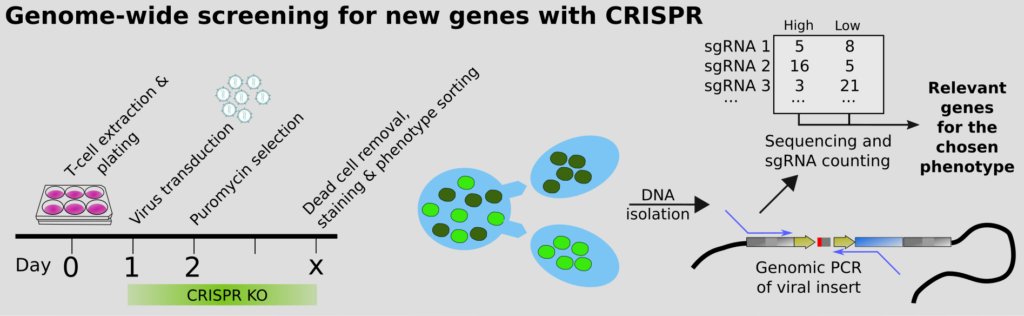

Our end-goal is to help understand all of biology. This can only be achieved by perturbing the system (i.e. knocking out genes), to see what happens. Classical screening for genes that regulate a biological process typically involves multiwell plates, but this is extremely expensive. The modern approach is to instead perform pooled CRISPR screens, which we were among the first to do, in the context of CD4 T cell differentiation; more recently also for the essentiality of genes in Malaria, together with Ellen Bushell. However, how to we guarantee that we get high quality scores for the phenotypes? We have developed an improved approach using molecular inversion probes (MIPs; also called padlocks). These overcome issues with PCR, such as GC%-bias, and enable precise counting of the originating DNA molecules. Statistics for NGS commonly rely on the negative binomial assumption, but we show that it breaks down when you work with a small number of molecules, leading to inflated statistics or simply bizarre conclusions. Complicating the molecular biology a bit thus seems motivated to maximize the value of pooled screens.

Can we improve our understanding of the immune system using modern single-cell technology?

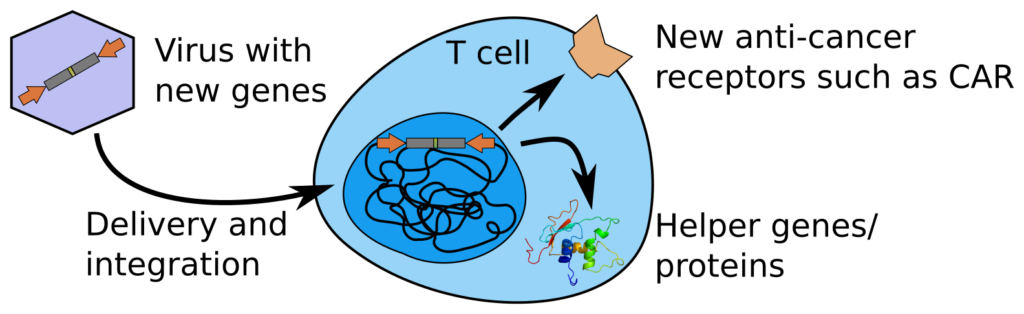

We have a particular interest in the immune system, especially to improve treatment of cancer. Using single-cell technology, with new readouts, we have especially found a new JUNB+ state of CD4 T cells. This state seems better delineated from an epigenetic standpoint rather than using transcriptomics. It seems intertwined with memoryness, as well as circadian rhythm and cell cycle, which somehow might explain why it is hard to separate. We however also find it in several previous single-cell atlases, and it is especially prevalent in exhausted CAR T cells. A better understanding of this state, which does not conform to the dogma of CD4 T cell subtypes, might thus be key to understanding several properties of T cells, including how to better make them fight cancer.

Our strong side is on the technology, and we are happy to be collaborating with others who contribute more classical biological know-how. This includes for example Isabelle Magalhaes for CAR T cells (T cells genetically modified to target cancer), and Nicole Boucheron for the T cell involvement in allergic asthma. We have also worked with Mattias Forsell on the related B cells, and Anna Överby for the innate immune response during TBE, and Annasara Lenman during SARS-CoV-2.

Can we better distill knowledge out of large datasets?

A huge problem with modern large-scale omics is that we generate huge amounts of data, but aren’t sure how to turn it into working knowledge. But what even is knowledge? We are investigating several routes, all involving machine learning; for example, we have developed a new framework Nando to predict gene expression (i.e. gene regulatory networks), and we have applied it to our T cell atlas. We are also investigating machine learning-based methods of mapping data to our cognitive model through novel latent space formulations and variational autoencoders (VAEs), in collaboration with Tommy Löfstedt. Based on our analysis of the bias of which genes we have uncovered, a constructivist approach to expanding our knowledge is likely motivated.

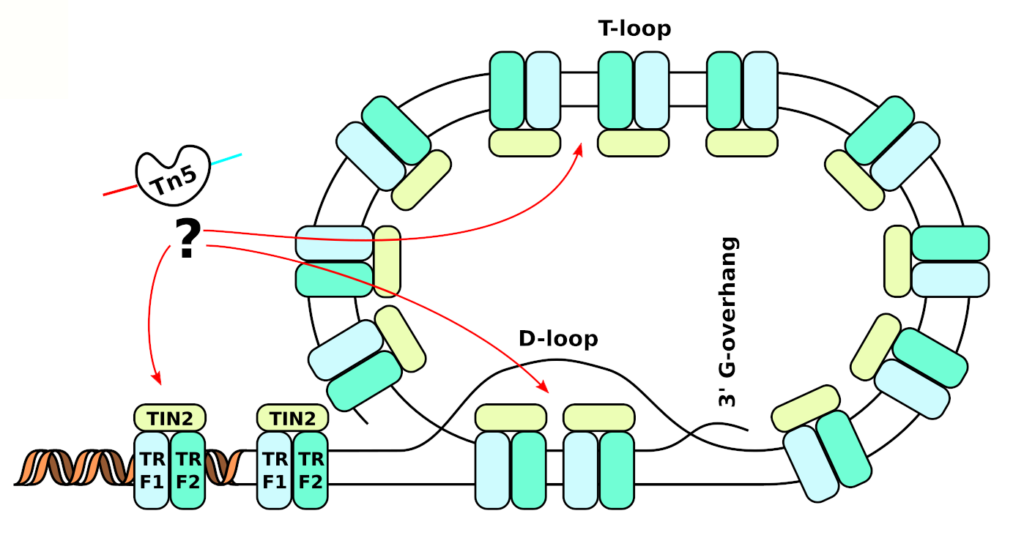

Can we find new uses of existing sequencing data? – Telomeres!

ATAC-seq is normally used to figure out where transcription factors are binding, and thus what drives gene expression pattern. We however argue that the tagmentation process (digestion by Tn5), the key to ATAC-seq, is not fully understood. Through exploration of the data, we have uncovered that telomeres are tagmented as well. Unfortunately, current ATAC-seq data only seem good for predicting the overall condensation state of the chromatin. In a project sponsored by Cancerfonden, we are now attempting to design a new protocol that is tailored toward measuring the length of the telomeres in each single cell. We envision that this can be used to provide earlier detection of cancer, as especially needed for pancreatic cancer (10% survival, 5 years after diagnosis).

Can we extend our technology to also work for microbes?

Single-cell technology has so far primarily been used on eukaryotes, because these have turned out to be somewhat simple to approach. Microbes are however at least as important. We are now collaborating especially with Laura Carroll, Kemal Avican and Linas Mažutis, using a new single-cell platform, to be able to also do microbial single-cell analysis. Stay tuned for updates!